Simply put, stress is “the experience of a challenging event”—not just the event itself, but the experience of it, the way your mind and body respond to what is happening.

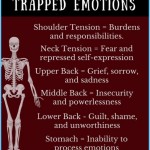

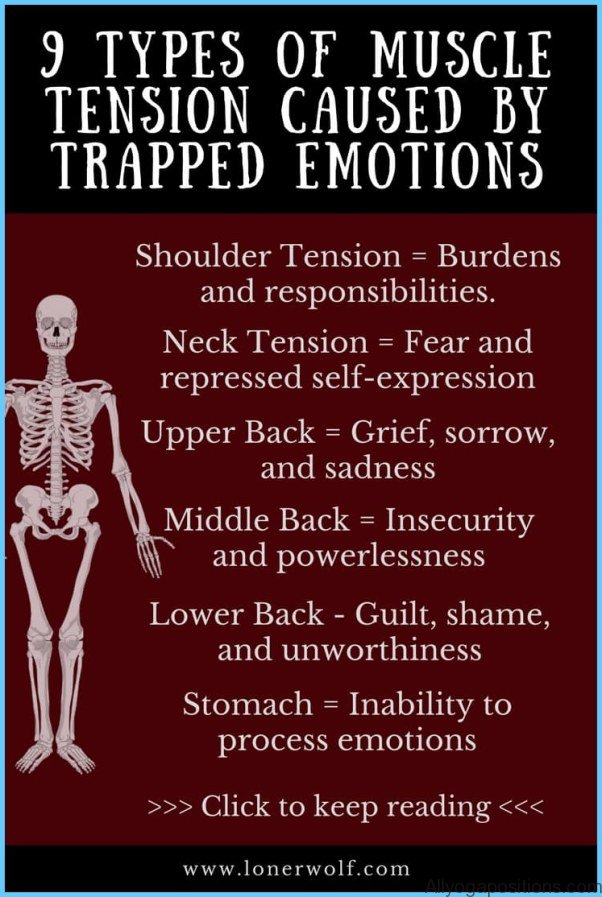

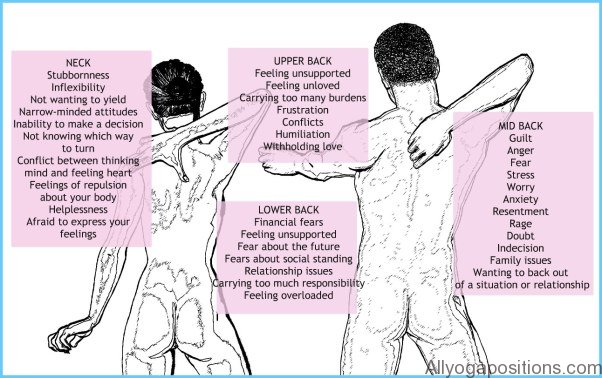

Stress can take different forms. It can be physical: Let’s say you’ve just been chased by a rabid dog, which left you with a pounding heart, barely able to catch your breath, and sweating bullets. It can be emotional: Imagine you’ve been forced to interact with a very difficult person. You walk away from the interaction with a pounding headache and an intense desire to scream or punch something. It can also take the form of a mental challenge: You can probably recall a time when you had to take an extremely difficult written test. As you worked your way through the questions, doubting your answers and constantly checking the clock, you probably felt beads of sweat forming on your forehead and the back of your neck may have tightened up.

Chronic Pain Creates Constant Stress Photo Gallery

These three forms of stress—physical, emotional, and mental—may sound like very different things. After all, during the physical stress of being chased by a rabid dog you’re racing down the street as fast as your feet will carry you. But the emotional stress of an argument may arise when you’re standing completely still. And the mental stress of taking a test creeps in when you’re sitting in a chair and the worst that could happen is you squeeze your pencil so hard it snaps in half. Yet to your body, all forms of stress represent danger and are treated the same way. No matter which form stress takes, your body instantly prepares you to either fight or run for your life. Whether you’re tumbling down a mountain side, being screamed at by an angry client, or desperately trying to think of the right answer, your body responds the same way.

Fight-or-Flight: A “One Size Fits All” Response

The moment your brain senses danger, no matter which form the threat takes, it triggers a cascade of physiological reactions that throw you into the fight-or-flight mode. In a just a split second, you are physiologically equipped to survive, either by fighting back or running away.

Think of a battleship floating peacefully across a fog-shrouded ocean in an old World War II movie. The lookout peers through a break in the fog and suddenly sees an enemy ship coming in fast, guns at the ready. Instantly, he hits the alarm button and a piercing shriek reverberates through the ship, jolting every sailor to action. All unnecessary activity comes to a halt as everyone who has been eating, napping, or swabbing the deck races to their battle stations. The engineers shut down unnecessary machinery and shift all power to the engines and guns. Messages fly back and forth between key parts of the ship, while other areas go silent. Guns are loaded and torpedoes are rammed into the firing tubes in record time, as the ship rapidly picks up speed, ready to engage in battle or blast on out of there. In just a few seconds, the ship has shifted from “cruise mode” to “battle mode.”

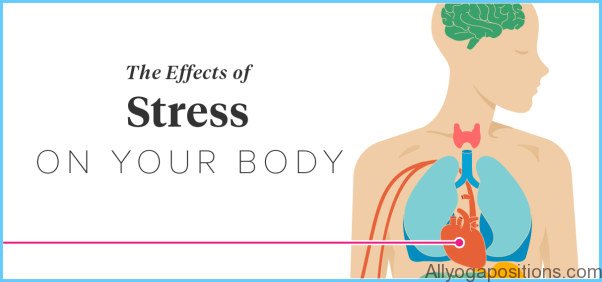

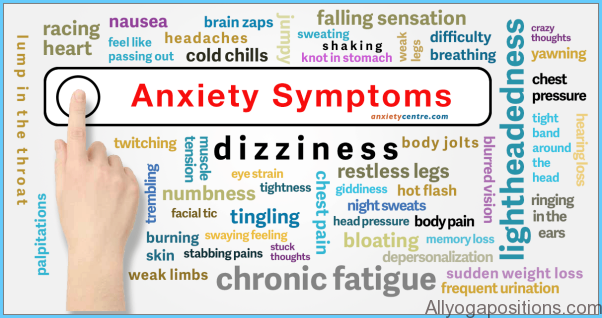

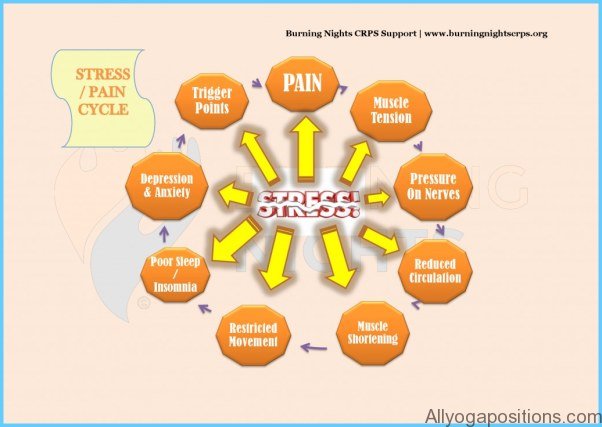

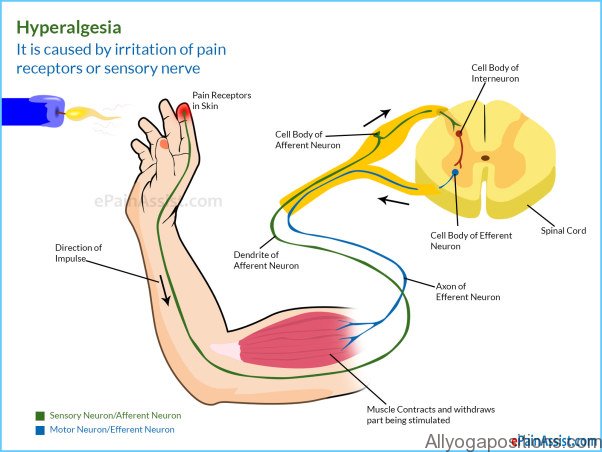

Something similar happens inside your body when it flips into fight-or-flight mode. It takes a lot of energy to fight or to run, so your heart begins pumping harder and faster, sending a rush of blood through your blood vessels carrying oxygen and glucose, the body’s fuel, to your body’s cells. Your breathing rate speeds up and small airways in your lungs open wide, so maximal amounts of oxygen get into your blood to keep up with the body’s increased demand. This also helps your body expel carbon dioxide generated by all of this sudden, intense activity. Your pupils dilate so you can see better, and your hearing and other senses become sharper. Indeed, your entire nervous system becomes more sensitive, making light look brighter, noises sound louder, and smells seem stronger. Your temperature rises as your body burns through fuel at a rapid rate; increased sweating will release this extra heat through the pores of your skin.

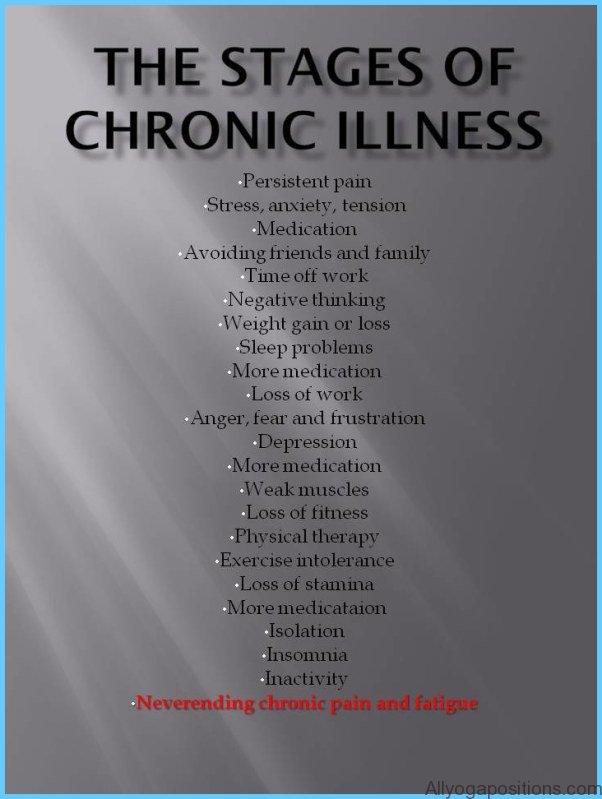

But not all parts of your body are energized, as not all of them are needed at the moment. You want as much blood as possible to go to your brain and the muscles in your arms and legs, so you can think, run, and fight. So the blood vessels to these and other key areas have opened wide, while less critical vessels, like those near the skin’s surface, have been temporarily throttled back, leaving your hands and feet feeling cold and clammy. And because it’s not absolutely essential that you digest the remnants of your breakfast or perform routine filtering of your body’s fluids at the moment, the blood flow to your stomach, kidneys, and certain other areas has also been restricted. For the same reason, activity in your pelvis and bowels has slowed, possibly causing cramping, constipation, and, in males, a lack of erection. Even certain immune system activities get curtailed, as facing immediate danger is more important than tracking down bacteria or dealing with cancer cells. Your survival at this moment takes precedence over everything else.

These and other changes happen in the blink of an eye, often before you consciously realize there’s danger. That’s why you may suddenly jump out of the way of an oncoming car before you’ve even recognized the danger. Or you feel flushed and hot and your heart pounds when you’re dealing with a difficult person, even though you don’t feel that you’re in danger.