Graves’ disease is an auto-immune condition that’s caused by an overactive thyroid gland. It occurs approximately five times more often in women than in men and is considered to be the most common cause of hyperthyroidism. Women who suffer from Graves’ disease experience symptoms such as rapid weight loss, increased pulse rate, sweating, nervousness, insomnia and a thickening of the skin on the shins. In 50 percent of all cases, Graves’ disease causes the eyes to protrude, due to swelling and inflammation of the tissues around the eyes. Fortunately, Graves’ disease can be controlled fairly easily. It is treated with anti-thyroid drugs, radioactive iodine or surgical removal of the thyroid gland.

WHAT CAUSES GRAVES’ DISEASE?

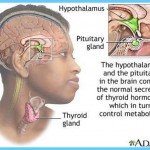

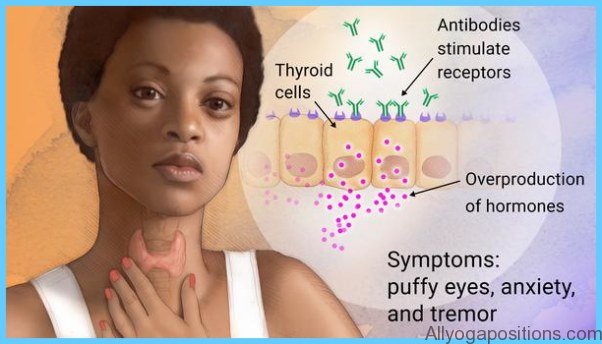

As you read above, your thyroid gland produces a steady supply of two major thyroid hormones, T4 and T3. When you are healthy, your pituitary gland, located in your brain, releases thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), which then triggers the release of T3 and T4. These thyroid hormones travel in your bloodstream to various organs in your body and determine the speed of all your internal chemical processes. In a nutshell, thyroid hormones act to control your body’s metabolic rate, the speed at which you burn calories. When T3 and T4 are at normal levels, the amount of TSH in your blood will level off.

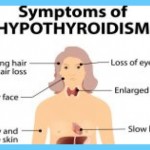

When your thyroid gland becomes overactive, it secretes too many thyroid hormones, causing your cells to work harder and your metabolism to speed up by 60 to 100 percent. This condition is known as hyperthyroidism and is characterized by a high metabolic rate. Hyperthyroidism causes a range of symptoms, including pounding heartbeats, profuse sweating, increased blood pressure, fatigue, weakness and general feelings of anxiousness, irritability and nervousness. When your levels of T3 and T4 are too high, TSH will be suppressed. Measuring the level of TSH in your blood allows your doctor to check your thyroid function and thyroid hormone levels.

Graves’ Disease Graves Hyperthyroidism Photo Gallery

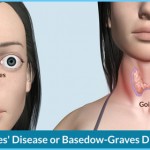

There are several factors that may trigger hyperthyroidism but, in North America at least, Graves’ disease causes 90 percent of all cases. This disorder is named after the Irish physician Robert Graves, who first described it in 1835. The condition is also referred to as diffuse toxic goiter, thyrotoxicosis or Basedow’s disease.

Graves’ disease is an auto-immune condition. Under normal circumstances, the immune system produces antibodies that protect the body from foreign invaders, such as bacteria and viruses. In Graves’ disease, the immune system malfunctions and produces a protein called thyroid-stimulating antibody that causes the thyroid gland to overproduce thyroid hormones.

At this point, little is known about the exact causes of Graves’ disease. Scientists have determined that Graves’ disease tends to run in families, but they don’t understand the circumstances that trigger the condition in certain individuals. It’s thought that severe emotional stress may be a factor. Stress can increase the blood levels of cortisone and adrenaline, two hormones that help prepare the body for a stressful event. Cortisone and adrenaline may affect the production of antibodies in the immune system. Yet many women with Graves’ disease have very little stress in their lives, which suggests that there must be other factors at work. It’s possible that environmental conditions may cause immune system malfunctions, triggering the problems of an overactive thyroid.

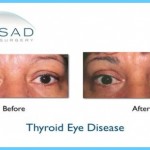

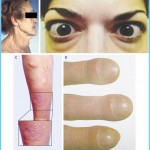

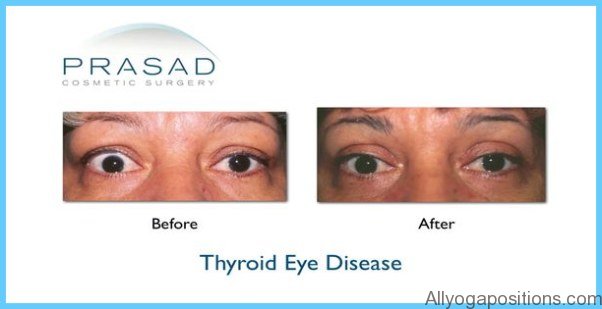

Graves’ disease has a strong association with eye disease. The antibodies that stimulate the overproduction of thyroid hormones also react with the proteins in the eye muscle, as well as the connective tissue and fat around the eyeball. This causes swelling and inflammation of the tissues, resulting in protruding eyes. Again, very little is known about the connection between Graves’ hyperthyroidism and eye disease.

Thyroid hormones also have an effect on the reproductive system. Women with Graves’ disease may find that their menstrual periods decrease, and younger girls may experience a delay in the onset of menstruation. For many women, an overactive thyroid gland is connected with infertility. Fortunately, once the condition has been treated successfully, fertility is usually quickly restored.

If left untreated, Graves’ disease increases the risk of miscarriage or birth defects and may, in rare cases, lead to death. However, if properly diagnosed, the condition can be safely and effectively controlled.

SYMPTOMS

Women with Graves’ hyperthyroidism experience many of the following symptoms:

• nervousness and irritability

• fast heartbeat

• sleeplessness

• heat intolerance

• high blood pressure

• increased perspiration

• shakiness and tremors

• muscle weakness, especially in upper arms and thighs

• confusion

• increased appetite

• weight loss

• frequent bowel movements

• eye changes, including puffiness and a constant stare

• sensitivity to light, increased tear formation

• fine, brittle hair and thinning skin

• lighter or less frequent menstrual periods

In addition to the symptoms of hyperthyroidism listed above, Graves’ disease is characterized by three other distinctive symptoms:

1. The thyroid gland may become quite enlarged, causing a bulge in the neck. This is called a goiter and develops because the immune antibodies overstimulate the entire gland.

2. Sometimes people with Graves’ disease develop a lumpy, reddish thickening of the skin in front of the shins, known as pretibial myxedema. If you develop this symptom, you will find that the thickened skin may be itchy and red and may feel quite hard.

3. Fifty percent of women with Graves’ disease will have eyes that protrude out of their sockets, due to a buildup of deposits and fluid in the orbit of the eye. As a result, the muscles that move your eye are not able to function properly, causing double or blurred vision. Your eyelids may not close properly because they are swollen with fluid, exposing your eye to injury from foreign particles. Most of the time, your eyes will be painful, red and watery.

Today, we all lead such busy and demanding lives that it’s easy to mistake the symptoms of hyperthyroidism and Graves’ disease for the normal signs of stressful living. The onset of hyperthyroidism is very gradual and it may take weeks or months before you realize that you are ill. The skin and eye changes associated with Graves’ disease complicate the situation even further, as they may appear long before or many months after the other symptoms of hyperthyroidism are identified. In some cases, the eye symptoms may continue to appear or become worse, even after the excessive thyroid hormone production has been treated and controlled. On the positive side, both the eye and the skin changes have been known to disappear without treatment, after a period of months or sometimes years.

WHO’S AT RISK?

About 75 percent of all auto-immune diseases occur in women, hitting them most often during the ages of 30 to 40. In the United States, hyperthyroidism from all causes affects approximately 2 percent of women, compared to 0.2 percent of men.

Diseases of the immune system also tend to run in families. Graves’ disease has been identified as an inherited condition, although not every member of an afflicted family will develop the disorder. Cigarette smoking may also increase your risk for Graves’ disease. One study found that, compared to women who smoked the least, those who smoked the most had a five-fold greater risk of developing the disease.1 The same study revealed that the risk of Graves’ disease was almost eight times higher among women with the highest stress scores.

Graves’ disease has also been linked with other auto-immune conditions, such as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, pernicious anemia and vitiligo.

You may be at risk of developing this type of hyperthyroidism if you

• are a woman between the ages of 20 and 40

• are a woman who has given birth within the last six months

• have experienced thyroid disease before

• have been overtreated for hypothyroidism

• have other auto-immune conditions

DIAGNOSIS

Usually, your doctor will be able to make an initial diagnosis of hyperthyroidism based on a history and investigation of your symptoms. The appearance of a goiter and protruding eyes are strong indicators of Graves’ disease.

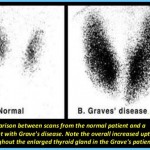

To confirm the diagnosis, your physician may suggest a simple blood test to measure the level of thyroid hormone in your bloodstream. If the laboratory results are unclear, a test to measure your blood levels of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) may be necessary. The TSH test is a very sensitive diagnostic tool and is often used to identify cases of hyperthyroidism, even before symptoms appear. Once hyperthyroidism has been diagnosed, your doctor may also send you for a CAT scan,

an ultrasound or an MRI. These tests are used to obtain a clear picture of your thyroid gland, which will help determine the exact cause of your overactive thyroid problems.

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT

The treatment for hyperthyroidism varies according to the needs and symptoms of each woman. In developing a treatment plan, your physician will consider your age, the severity of your illness, the symptoms you are experiencing and other medical conditions that you may have.

There are three main approaches to treating the problems associated with hyperthyroidism and Graves’ disease.

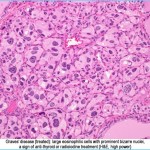

1. Medication Anti-thyroid drugs such as Tapazole® (methimazole) are most commonly used to treat hyperthyroidism. They slow down the activity of the thyroid gland by suppressing the release of thyroid hormones. The doses of these medications are adjusted according to the level of thyroid hormone in your blood. Anti-thyroid medication will usually bring your condition under control if taken for a period of six weeks to three months, but it may be necessary to continue taking the drugs for months or years to ensure that your disease stays in remission. If you stop taking the medication, there’s a 50 percent chance that your disease will flare up again. Anti-thyroid drugs are usually prescribed in mild cases of hyperthyroidism and in cases where the disease affects children, young adults or the elderly. Occasionally, these drugs may cause mild allergic reactions, such as rashes, hives and nausea. In very rare instances, anti-thyroid medication may dangerously lower your white blood count, making you susceptible to serious and potentially life-threatening infections.

2. Radioactive iodine Since anti-thyroid drugs do not cure hyperthyroidism, you may be treated with radioactive iodine to achieve a long-term solution. A small dose of radioactive iodine is taken by mouth and travels from your stomach to your thyroid gland, where it destroys some of the cells. Only a very small amount of radioactivity is introduced into your body with this treatment, and it disappears from your system without any harmful effects in a matter of hours or days. Treatment is usually designed to destroy only enough thyroid cells to bring thyroid hormone production back to a normal level. In reality, though, treat- ment with radioactive iodine usually causes your thyroid gland to slow down to the point where it underproduces thyroid hormones, creating hypothyroidism. Hypothyroidism is easily treated by taking a daily thyroid hormone pill called Synthroid® (levothyroxine) to restore normal blood levels.

3. Surgery Hyperthyroidism can be permanently cured by surgically removing your thyroid gland in a procedure called a thyroidectomy. This is an option to consider if you have a large goiter, if you have a negative reaction to anti-thyroid medication or if you are in a younger age group. Once your thyroid gland is removed, the cause of your hyperthyroidism is eliminated. In most cases, surgery will control your symptoms, but you may require thyroid replacement pills for the rest of your life.

In addition to these treatment options, your doctor will usually prescribe beta-blocking drugs such as Inderal® (propranolol), Tenormin® (atenolol) and Lopressor® (metoprolol). Beta-blockers do not control your abnormal thyroid function, but they are very useful in managing symptoms, such as increased heart rate and nervousness, until other forms of treatment can be started. These drugs block the action of the thyroid hormone circulating in your bloodstream, slowing your heart rate and reducing feelings of nervousness and irritability. They are not suitable for people who have asthma or heart failure because they may cause these conditions to become worse.

Fertility

Women who have been treated for Graves’ hyperthyroid usually have no difficulty becoming pregnant, since normal fertility is restored once the condition is under control. If you’ve been given radioactive iodine, you should wait six months after treatment before becoming pregnant.

If you are pregnant and require treatment for Graves’ disease, you should be aware that radioactive iodine treatment is not recommended during pregnancy and surgery, and should be avoided for fear of causing a miscarriage. Because pregnancy has a suppressive effect on the immune system, you can consider treatment with a low-dose anti-thyroid drug. However, be careful to avoid larger doses, as these medications can cross the placenta and affect your baby’s thyroid gland. Radioactive treatments should also be avoided while breastfeeding, but anti-thyroid drugs in lower doses appear to be safe for both nursing mothers and babies.