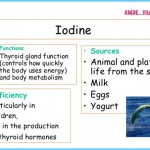

This trace mineral is an integral part of T3 and T4, the two thyroid hormones released by the thyroid gland. Our major source of iodine is the ocean—seafood and seawater are excellent sources of the mineral. As you move further inland, the amount of iodine in foods varies and generally reflects the amount in the soil that plants grow in or animals graze on. Land that was once under the ocean contains plenty of iodine. In the United States and Canada, the soil around the Great Lakes is iodine-poor. However, the fortification of table salt with iodine in America has eliminated health problems caused by iodine deficiency.

If your body were short-changed of iodine on an on-going basis, the production of thyroid hormones would slow down. This would eventually lead to hypothyroidism. But if you eat salty processed foods and fast foods, or if you add table salt to your meals, you’re certainly not at risk for consuming too little iodine.

VITAMINS AND MINERALS Iodine for Thyroid Disease Photo Gallery

It may seem odd, but too much iodine in the diet can also cause hypothyroidism. Excess iodine can result in low thyroid hormone levels by halting the activity of enzymes needed for their production. There have been cases of people who develop hypothyroidism by taking in too much iodine in the form of iodine-rich seaweed and kelp on a daily basis.

Obviously a lack of iodine will not lead to Graves’ hyperthyroidism. But if you do have Graves’ disease, short-changing your diet of this indispensable mineral might influence your remission rate after treatment with anti-thyroid drugs. An American study of 69 patients who took anti-thyroid medication for Graves’ disease suggests that the more iodine in the diet, the longer the rate of remission, or how long the disease remained dormant.2

The daily recommended intake for iodine is 150 micrograms per day. During pregnancy and breastfeeding, women need to consume an additional 70 and 140 micrograms each day, respectively. North Americans are estimated to be consuming 200 to 600 micrograms of iodine per day, well above our requirements. Some of this iodine excess may come from our growing dependence on fast and processed foods, since these foods contribute a generous amount of salt to our daily diet. Besides iodized salt, other food sources of iodine include seafood, bread, dairy products, plants grown in iodine-rich soil, and meat and poultry from animals raised on iodine-rich soil.

If you have Graves’ disease and anti-thyroid drugs are a part of your treatment regime, make sure you include iodine-rich foods in your diet. This is particularly true if you live in an area with iodine-poor soil, if you avoid fast food and salty foods, and if you don’t add table salt to your meals. Consider bringing back the salt shaker—a little is all you need; don’t exceed 600 micrograms per day.